Gerald G. Grant, Ph.D. and Robert Collins

The Canadian government is again in the mainstream news over shocking failures in their IT efforts. Headlines such as CBC News’ “Phoenix pay system mess affects 80,000, government officials say” will continue to be written if managers and technical people implementing such systems don’t change the way they think. The failures reported are just the latest is a long line of challenges faced by public sector organizations seeking to transform the way they work by implementing advanced information technology systems. Many similar efforts gone awry include the Social Assistance Management Systems (SAMS) in Ontario and the now infamous failed roll-out of the Healthcare.gov website in the United States. Challenges with large-scale systems implementation are not confined to the public sector as some would have us believe. There has been and continue to be many similar failures in the private sector (for example Target Canada).

So why do we keep seeing these failures? We do because, often, everyone involved in the process of authorizing, procuring, implementing, and using these enterprise-wide systems approach the effort as a large-scale engineering project. With an engineering mindset there is an expectation that all the parameters are known and can be accounted for. Change is the enemy and must be eliminated at all cost. In thinking like engineers, both business and technical people often focus on the technical implementation of systems without giving sufficient attention to the social and behavioural aspects of transformation enabled by digital systems. It is very telling that the deputy minister of Public Services and Procurement, Marie Lemay, told the CBC that “the government grossly underestimated the time and training needed to move to the new system and clear out old cases”. This should never be the case. Surely by now, we have enough experience and research that tell us that the hardest part of system transformation efforts is not the implementation of the technical system but getting the organization to integrate the systems into new ways of working. So when cuts are made to training and transformation processes, dates and times become non-negotiable and tyrannical, we end up with the debacles we now see.

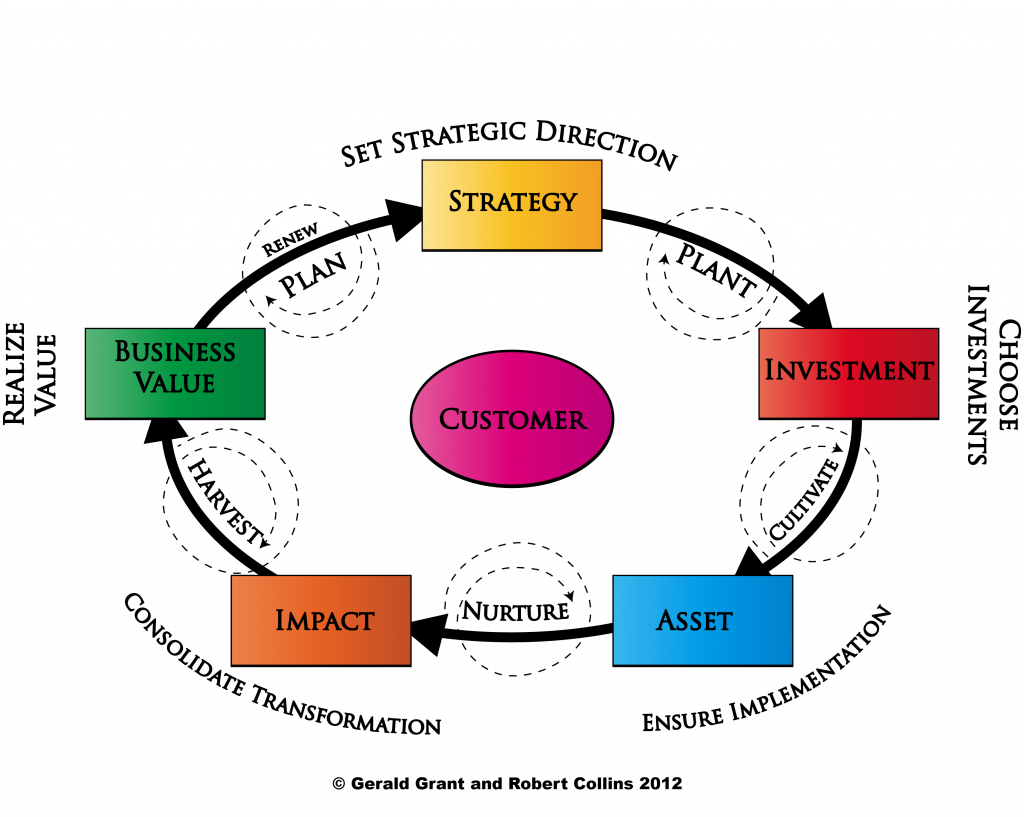

In our new book, The Value Imperative: harvesting value from your IT initiatives (available on Amazon.com) we address how organizations can avoid the mistakes we see so often. We propose that instead of thinking like engineers, business and technical people involved in systems enabled transformation efforts should think more like farmers. Farmers do not solely focus on getting the seeds planted and irrigation systems implemented. They focus on bringing home the harvest. If they do not cultivate, nourish, and actively harvest the crop there will be nothing to bring to market. Rather than concentrate solely on getting the technical system implemented, managers should instead focus on the value sought. In the Phoenix project case, the value sought is efficient, on time, and reliable payment of government employees at a reduced cost. This cannot happen simply by implementing the technical system. The major work to get the “harvest” delivered takes place after the technical system is delivered. To do this you need to have the right people doing the “harvesting”. Poorly trained staff unfamiliar with the processes won’t cut it. So often, on time, on budget system implementation is celebrated by bonuses and awards to the neglect of getting the system to deliver the expected impact. When such failures occur we see headlines blaming the “system”. The system may have its teething problems but often it is how the system is used (or not used) that is the major issue. In our book, we discuss the Value Realization Cycle. We believe that if both business managers and IT people understand, more fully, the ideas and implications of the cycle we will have less and less of these sensational headlines about IT-enabled system failures.