By Gerald Grant, Ph.D.

December 7, 2016

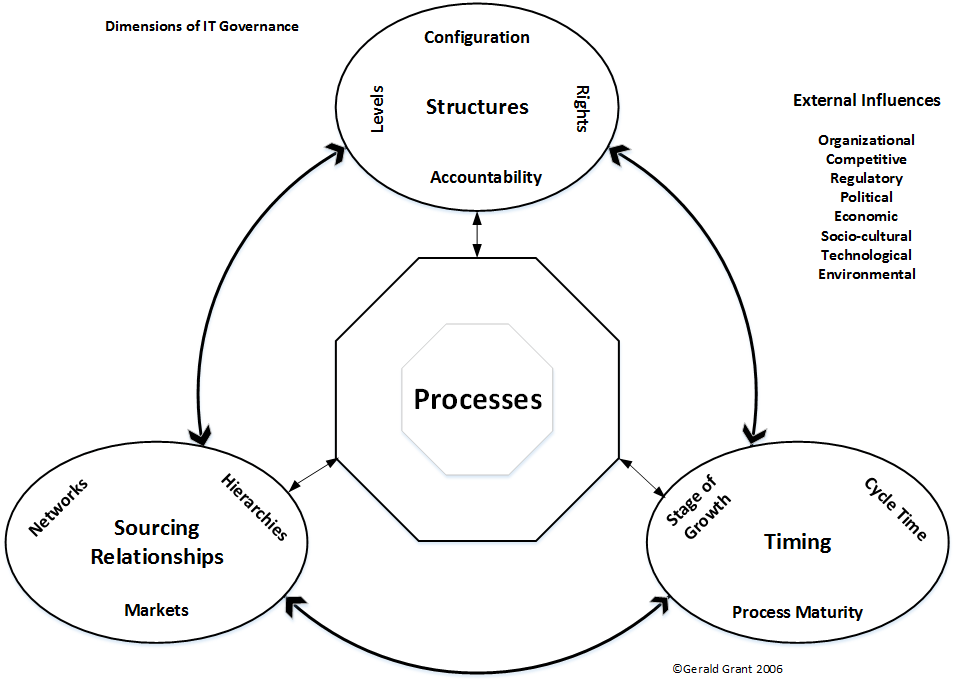

When organizations experience large-scale failures in the implementation of IT projects there is often a knee-jerk reaction to blame the technology or poor project management practices. Witch hunts are regularly conducted to find the “real culprits” or persons responsible. However, lurking behind most failed IT project implementations is poor or dysfunctional IT governance. Often, when the word governance comes up, those involved think of and talk about the structural properties associated with the term. Governance in many minds involves ensuring the right configuration of organizational relationships (centralized, decentralized, federated), the articulation of the various levels of employee reporting (boards down to operations), the delineation of accountability structures (who is accountable for what outcomes), and the identification of rights (decision, input, or consultative). All these feature prominently in discussions of governance with the implication that is they are done right good governance will result and organizations will achieve successful outcomes.

However, good IT governance goes beyond articulating, accounting for, and ensuring the successful enactment of these structural elements. It is not a static process. It is a dynamic and fully engaged process shaped by considerations of the structural properties, the nature of service provisioning relationships, the characteristics of the actual processes that must be executed to deliver value, the temporal characteristics that shape the pace and direction of managerial action, and the influence of the general environment in which organizations operate.

Executives need to understand that applying the same approach to IT governance when services are delivered internally (hierarchies) will not work when services are bought from external providers (market). IT governance for organizations providing IT services internally will be different from that in organizations buying cloud-based IT services from providers such as Amazon and Microsoft. Each requires different considerations for investments and operations. Each requires different types and managerial and operational skills as well. Services provided through shared arrangements (networks) must also be governed differently. In such engagements, performance cannot be demanded as they can from internal employees or threatened with non-payment for breach of contract as with market providers. It emerges through mutually beneficial collaborative action.

Governing IT for organizations that are mature will be different than in organizations that are in the early stages of growth. Mature organizations will more likely focus more on leveraging their IT investments than building up IT capacity, more likely with early stage or growing companies. Cycle times from order to delivery is different in process-based resource industries than in high technology consumer-driven industries. Missed deadlines in consumer high-tech are likely to be severely punished by loss of sales and market share. IT implementations in high-tech must, therefore, be more rapid and cannot be extended like those in industries with longer cycle times. Another aspect with temporal implications is the level of process maturity in the organization. Some organizations have very low process maturity (typically found in newer, less mature firms). Others have very optimized and sophisticated ways of executing their processes. Each will need to approach IT governance differently.

Good IT governance must be enacted in practice. Many organizations have the façade of good IT governance because they have the right structural diagrams posted on their walls. Governance in practice is manifested in the processes and mechanisms that practicing managers and others execute on an ongoing basis. Boards must account for value delivery, risk, and compliance with regulatory and policy requirements. Executives must set the strategic direction and define the parameters for architecture, portfolio prioritization, and sourcing. Managers need to provide effective project oversight, asset stewardship, and ensure effective change and service management. Poor execution of these processes will lead to failures in governance no matter the structure.

The environmental milieu in which organizations exist will shape the overall nature and character of IT governance. Some things won’t be possible if prohibited by law. Some ways of doing business will be dictated by industry characteristics and practices as well as the economic and political realities faced. Governance has to be responsive to these exigencies.

All of this means that good IT governance is not a one-size-fits-all endeavor. It has to be tuned to the nature and characteristics of the organization in which it is enacted. It requires careful consideration and effective action. It is a dynamic and performance driven process. Consequently, “cookie cutter” IT governance “solutions” are not possible. Such solutions are the current day equivalent of snake oil peddled by naïve or unscrupulous sales consultants. Don’t’ buy it!